On April 24th, 1963, the Boston Celtics took the floor at the Los Angeles Sports Arena holding onto a 3-2 advantage in the NBA Finals against the Los Angeles Lakers. For the only time in the history of the league, a Finals team trotted out only (later to be named) Hall of Fame players: Bob Cousy, Bill Russell, Tom Heinsohn, Tom (Satch) Sanders, Frank Ramsey, KC Jones, and John Havlicek. The previous season saw the Lakers go to a game seven overtime against the Celtics before falling to give the Celtics their fourth consecutive NBA Finals. The game was marked as “Bob Cousy’s Final Game as a Celtic” and was the final game of rookie John Havlicek’s season.

The Lakers only boasted two future Hall of Fame players in Jerry West and Elgin Baylor, but had an ensemble of steady players such as Rudy LaRusso, Frank (Pops) Selvy, and rookies Gene Wiley and Leroy Ellis. Common in the era, NBA offenses ran through the pivot position, which then was a mix of high and low post action that initiated an offense. While this was the primary offensive initiation for the Celtics, the Lakers frequently ran without a pivot position in an effort to create spacing in the lane for both West and Baylor.

In this post, we take a look back at Game 6 of the NBA Finals and break the game down with the ability to look back, building a play-by-play file and then analyzing how, for at least one game, the game was played at its highest level.

The Box Score is Bad: Let’s Build One Instead

Back in 1963 the only recorded statistics were field goal attempts, field goals made, free throw attempts, free throws made, rebounds, assists, and fouls. However, many games went without rebounds or assists recorded. For instance, the Boston Globe was unable to report on the Celtics’ Championship when it came to assists or rebounds. Despite multiple pages about the Celtics’ Championships win, this is what it had to say about the number of rebounds logged:

Boston Globe April 25, 1963. In an industry of “quantify, quantify, quantify” they couldn’t do that without an official count.

That’s right. There is no mention of actual counts of rebounds and assists. In a follow up with the league, we found that there was no evidence of an official count of rebounds and assists from the game. The box score of the game is actually a copy of the Basketball Reference box score, which also was unsure of where the official rebounds and assist tallies came from.

For instance, if we take the actual number of field goal attempts from Jerry West in the game and subtract the number of blocked field goal attempts, we obtain 24 attempts; the basketball reference number. This was true for a number of players in the game.

For rebounds, there were 12 live-ball free throw rebounds and, according to Basketball Reference, a total of 114 possible rebounds. As only 96 rebounds were recorded, this suggests that there should be 18 team rebounds; there were only 10 instances where rebounds either went out of bounds; or there was a no turnover foul (team rebound through a loose ball foul). Which means at least 8 rebounds are left completely unaccounted for. And that’s if field goal attempts were counted correctly. This suggests are number of rebounds are actually left unaccounted for.

So instead of belaboring a well-known issue with statistics prior to 1975, let’s walk through the game as tally all the data. Of course, in doing so, we will also get certain things wrong; such as assists. While, we are accustomed to use our NBA front-office training to mark assists; assists were counted much differently in the 1960’s. Some that should have never been accounted (instances where two players have passed the ball were both credited with assists) and some where they should have been counted (tapped passes leading directly to a score) will be “corrected.” That said, we will follow the guidelines of the 2010’s to credit rebounds and assists.

With that caveat in place, let’s dive into the game!

Boston Offense: Fast Break and Elbow Chase

The Celtics offense consisted of a steady diet of fast breaks in an attempt to catch the transition defense napping. At this time, whenever a team loses possessions either through a made basket or a turnover, every player would look for an outlet near half-court; or streaking down the sideline. For example, Elgin Baylor terminates a Lakers possession through a made basket and Bill Russell promptly clears the baseline to chuck the ball fifty feet to Frank Ramsey to take a chance on a 1-on-1 fast court break.

Unfortunately, Jim Krebs is able to deter the attempt and Frank Selvy secures the defensive rebound. The total time of possessions lasts for 5 seconds; which is not uncommon for Boston fast breaks. Throughout the course of a game, Boston will attempt to run at least 40 (!) of these possessions.

Typically, there will be two “gunners” with the secondary streaker to serve as the rebounder. While it is common for folks to claim that Bill Russell was the rebound man; it’s actually fairly rare for Russell to serve in this role. It’s simply that players such as Heinsohn, Satch, Jones, Havlicek, and Ramsey would be the ones gathering 2-3 of these a game giving the Celtics these extra chances. Russell’s offensive rebounds came more out of their half-court set; which today resembles the Throw and Chase and Elbow Continuity offenses.

The Throw and Chase offense is a simple, straightforward early offense designed to make the defense react before being set. It is the crux of the Pistol Offense, particularly the 21 series. Used in the half-court set by the Celtics, the throw and chase sets up a three man offense. For example, in this cut Bob Cousy initiates the offense with Tom Sanders and chases the pass. Most times, Cousy does not screen but rather goes over the screen to receive the ball right back.

In this action, the goal is to force the defense to either switch or stagger the defenders. Some of these attempts will find Cousy taking the 15-20 jump shot. When the exchange occurs, Bill Russell will either set high in the post or low in the post. If Russell sets high, these will almost certainly be a backdoor cut by Cousy:

However in the first clip, he sets low. If Cousy doesn’t take the pull-up jump shot, he will either pass to Russell in the post, pass back to Sanders if Sanders’ man sags that becomes a Sanders jump shot. If not, Sanders will screen away, pulling a weak side offensive player in a curl action (much like the Elbow curl in today’s game) which becomes Havlicek’s bread and butter in this game. This will also be Russell’s kick-out as he rarely takes shots in the interior from an initiated offense.

The fifth man’s role is to serve as a weak-side rebounder; which will turn out to be the most crucial play of the game: Heinsohn’s weak side offensive rebound on an errant Cousy attempt with 30 seconds remaining, early in the shot clock, and the Celtics only up one.

Using these three initiations, we have effectively 90% of the Boston Celtics’ offense diagnosed.

Los Angeles Offense: Spacing, Spacing, Spacing

If you ever had to pick a duo who resembled James Harden and Russell Westbrook when it came to offensive dynamism in the 1960’s, Jerry West and Elgin Baylor were your men, respectively. If there ever was a “tightly contested yet high efficiency” metric, it has to be named after Jerry West. Almost every shot taken was a difficult shot:

Despite that, early on in the game, West knocked down 6 of his first 9 field goal attempts and got to the line three other times to help propel Los Angeles to a 35-33 lead. A common method to get ball handlers open was to employ the Pick and Roll (PnR) offense. For example, after West started getting targeted by Russell on defense, West kicked out the ball to Rudy LaRusso, who receives a screen from Gene Wiley.

Almost always, defenders go under these screens, which LaRusso takes advantage of and knocks down the jump shot. In fact, LaRusso came out the gate hot in Game 6 as well, hitting on 9 of 14 jump shots; including his first five all from 15+ feet out. Midrange be dead, our butts.

However, with Wiley running the PnR, there would be no “pivot” player. In many games in the 1960’s involving the Lakers, announcers would charge the Lakers as being unorthodox as every team ran with pivot action. Instead, the weak side guard would be played by Hall of Fame forward Elgin Baylor, who would slash and attack the lane with reckless abandon.

Unfortunately, almost every slashing attempt was thwarted in the game by Tom Sanders, who’s primary duties were to keep Baylor from getting into the lane. Due to this, Baylor was held to a mere 3-for-11 from the field before changing game plans and finishing 8-for-12 in the second half by hitting several jump shots (and a couple hard fast breaks, splitting 2-4 defenders).

Shot Distributions

For Game 6 of the 1963 NBA Finals, we observed the following shot distribution for the Boston Celtics.

Distribution of Celtics’ Game 6 Makes (Green) and Misses (Blue).

Keep in mind, with technology from the 1960’s and the use of a three camera system that “flipped” from “theater” mode (wide screen mid court capture) to “narrow” mode (zoomed in on the ball handlers in the half court), many of the points are between 1 to 3 feet off from truth. Also, keep in mind, that lane is narrower in 1963 than it is today. Thank Wilt Chamberlain for that rule change in years to come.

However, this shot distribution is completely expected with hook shots from the left side of the court (as Bill Russell is a left-handed player and dives into the basket on attempts), several upon several 15-20 jump shots from around the free throw line, and many layups from the break. It is borderline unfair to see that much green in the midrange. But then again… it is the 1963 Celtics.

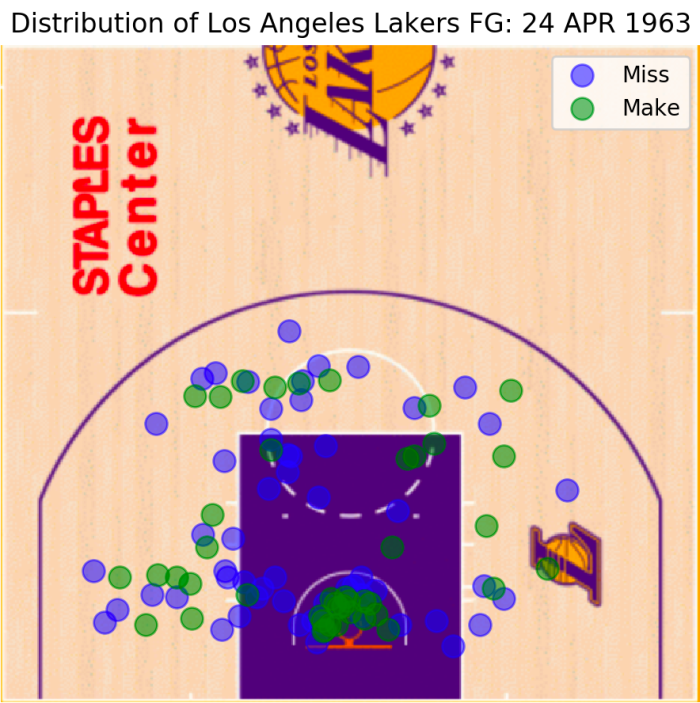

Distribution of Lakers’ Game 6 Makes (Green) and Misses (Blue).

For the Lakers, we see a lot of right handed attack. That’s the tag-team of Jerry West and Rudy LaRusso. The rim green is a relentless assault from Jerry West during the game and some fast break attempts.

What we see here is the Bill Russell effect. Which means shooters avoided Russell in the paint at all costs. Taking away the layups, which were West/Baylor doing Hall-of-Famer things or fast breaks, you’ll notice that there are only a meager two made field goals within 10 feet of the hoop. A staggeringly low 2-FOR-20 against the Celtics in the short mid-range.

Now before you say “great gadzooks!” at this number, the Celtics were only 6-for-22 in the same region (3-10 feet from the basket in non-transition attempts), led by Russell’s 1-for-7 attempts in this region.

However, before we laud Gene Wiley as being a “Russell Stopper,” we have to take note of the Celtic’s game plan before we walked down this basic analysis: Russell was used as a gravity player. The Lakers would double team Russell to keep Wiley and Jim Krebs out of foul trouble. It would also place a second rebounder in place if needed. Therefore, the Celtics would use Russell to create spacing from the Pass-and-Chase strategy to get open looks. This would allow to get offensive rebounds as well; provided they were hitting their open looks.

So while we see the Russell effect in place against the Celtics, the shot chart doesn’t tell anywhere close to the whole story.

Four Factors

At the game level, it’s important to know how well you terminated your and your opponent’s possessions. Recalling that the four factors are eFG%, REB%, TOV%, and FTA/FGA, we effectively ask the following:

– How did we compare to our opponents when we both got shots off?

– When we missed attempts, who was better at rebounding?

– Are we able to eliminate more field goal attempts than our opponents?

– Are we able to get to the line more frequently than our opponent?

If you win 3 of those categories, you have a great chance of winning the game. For Game 6 of the 1963 NBA Finals, here were the four factors:

Effective Field Goal Percentage: Boston .4607, Los Angeles .4400

Boston narrowly edged out the Lakers in eFG% for this game, which means if they held constant in turnovers, rebounds, and FTr, the Celtics were expected to win by roughly four points.

Offensive Rebounding Percentage: Boston .3571, Los Angeles .2982

Offensive rebounding was at a high rate in this game: 35.71% of potential rebounds on a Celtics’ possession ended up back in Boston’s hands. To put this in perspective, for 100 possessions, we expect 54 possessions to miss. Boston’s OREB% gives them another 19 chances. Continuing on with this logic, that’s another 9 made baskets and 4 third chances. This yields another 2 made baskets. An expected value of roughly 22 extra points in the game!

And while Russell led all Celtics with 5 offensive rebounds, the Celtics piled on 20 total offensive rebounds in the game; not including team rebounds. It is interesting to see that Jerry West and Gene Wiley had as many (or more) offensive boards as Russell had in the game. Adjusting the 100 possessions accordingly, and hitting this with that geometric distribution diagrammed above for the Lakers, the Celtics were expected to win this game now by 8 points.

Turnover Percentage: Los Angeles .1045, Boston .1176

Here the Lakers won this category by collapsing on Russell in the paint and forcing bad passes, for four total, or taking charges, for five total. That’s right, Los Angeles drew six offensive fouls from the Celtics, five of which were charges.

Using the logic above, this “reduces” the Lakers’ deficit from 8 points down to 5 as 1.3% of chances are now missing (cannot be attempted or rebounded).

Free Throw Rate: Los Angeles .2100, Boston .1764

During the course of the game, the Lakers got to the foul line 20 times, while the Celtics got to the line 18 times. For the uninitiated, during the 1960’s every defensive foul resulted in a free throw attempts. There was no “Bonus” in the way we think of it today. In fact, Boston would employ a “Two-for-One” tactic where they would immediately foul the ball handler, knowing they could only get one free throw attempt and Boston would get the ball back.

Up 10 with a minute to play? Foul.

Down 1 with 10 seconds left? Foul.

When a team reached 6 team fouls in the quarter, however, teams would then receive a “Penalty” free throw; which is an extra free throw. Fouled on a layup in the penalty? Three free throws!

Despite this tactic, the Lakers drove up the free throw rate to a tune of obtaining a +3 expected value.

Combining all four factors results in an expected 99-97 Celtics win for 100 possessions. Extending out to the 116 possessions played by each team, the Celtics were expected to win 114 – 111. The final score? 112 – 109.

Updated Box Score

We can now update the box score, which is given as:

Updated Box Score using video!

Here, we see some adjustments on the official count. For instance, all rebounds are accounted for. Adjustments using the “shot taken within 2 dribbles of receiving the ball” assist counting method is used; which, for the record, reduces some players’ totals…

But we are now able to obtain actual playing time, blocks, turnovers, and steals. We can also see how players scored, such as points scored off assists (PoA) and how many points that player assisted on. In particular, Jerry West contributed to

More importantly, we can start looking at items such as points contributed.

Points Contributed

Using the running net points (adjustment of player contribution using the points produced model), we can see the contribution of each player throughout the game. For the uninitiated in this metric, this is not “all encompassing” but rather a play-by-play stat devoid of factors such as gravity, Russell effect, and other “tracking” based metric that helps fills in the cracks. That said, points contributed backs up some interesting points that did indeed occur within the game.

Points Contributed for the Los Angeles Lakers.

Here we see that West and Baylor are indeed the leading men for the Lakers. However, Sanders’ tight defense, coupled with LaRusso’s incredible first quarter left Baylor as a relatively ineffective player. We also see Gene Wiley wear down over the course of the game; as one would inspect having to guard Bill Russell for 35+ minutes.

The key player that gets lost in the mix is Leroy Ellis. As the Celtics outran the Lakers in the second quarter (we will get to this shortly), Ellis played in significantly little time. At the start of the second half, Ellis replaced Frank Selvy in the lineup. This meant the Lakers traded in a veteran point guard (Selvy) for a rookie “Power Forward.”

Using this big lineup, the Lakers muscled in the paint, contested the outside jump shots, and drove the Celtics into a frenzy. With Ellis hitting a couple key shots and picking up a couple Celtics fouls, Baylor was able to start finding space to knock down three critical shots to help turn a 12 point deficit into a 4 point deficit. Of course, that was until John Havlicek found his touch from the outside.

Points Contributed for the Boston Celtics.

In Boston’s running net points model, we see Havlicek race out to be a significant contributor in two segments of the game: 1050 – 1440 seconds (final 3:30 of the first half) and 1700 – 2100 (another 3:30 window late in the third quarter). In fact, during the third quarter rally from the Lakers, Havlicek knocked down a couple key baskets to thwart the Lakers runs.

However, the subtle story of the game was KC Jones as he played the first nine-and-one-half minutes of the second quarter after coming in for a slow-to-start Sam Jones. KC Jones made the most of his time, pushing the tempo back up. Scoring 9 points on 8 chances and diming out six assists; Jones became responsible for 21 of the Celtics’ 33 second quarter points en route to a LA Sports Arena deafening 16 point brow-beating of the Lakers.

Not only did Jones’ contribution turn the tide of the game, it forced the Lakers to play “Big” the following half; the primary reason Jones sat out much of the second half in favor of Frank Ramsey and John Havlicek.

Given all of this, we also see Tom Heinsohn’s late game heroics by finishing 4-for-5 from the foul line, snagging a key jump ball (defensive rebound for Russell by proxy), and nabbing a big offensive rebound with the Celtics only up one points with 30 seconds remaining.

While the story was about Cousy (named as player of the game at the end of the broadcast) and Russell’s dominance, the story of the game was the “role player” for the Celtics. The other six Hall of Famers that chipped in when Russell was doubled, pushed around, attacked relentlessly, and Cousy went down with an temporary injury.

And now we have evidence of this game as a play-by-play log:

Sample of the play-by-play log for Game 6 of the 1963 NBA Finals.

In the words of another famous Celtic legend: Merry #&$*! Christmas.

Other Notes:

– Bill Russell finished with 8 blocks. Five of them were against Jerry West. The others were Dick Barnett, Rudy LaRusso, and Jim Krebs (each once).

– Every single one of Bill Russell’s blocks ended up in someone’s hands: no team rebounds. Six returned to Celtics players, two of them to Russell himself. Typically 3 of 8 is seen as good. 4 of 8 is great.

– This game has featured 10 Hall of Fame players.

– This was not Bob Cousy’s final game in the NBA. Despite retiring after this game, Cousy played in 7 games for the Cincinnati Royals in the 1969-70 season. Seven years later.

– Both John Havlicek and Bob Cousy suffered injuries. Havlicek took an elbow to the mouth but did not come out of the game; Boston later called time out to stop the bleeding. Cousy sprained his ankle early in the fourth quarter, but returned with four minutes remaining.

Hello Justin great article, where did you access this footage? Would absolutely adore the oppurtunity to watch Bill Russell play defence

LikeLike

Great job. Did they really get 3 shots when shooting in the penalty, or was it a 3 to make 2? They did get a bonus if they missed, but didnt know/think they could actually make 3 points. Also surprised the turnover % were so low for each team.

LikeLike

You’re right: It was 3-for-2. The emphasis was that there was three foul shots available. Which looking back, does make it sound like a possibility for three points. Sorry about that, but thanks for making the footnote here in the comments in case other readers see it that way.

The TOV% is indeed pretty good. Teams today range between 11-to-14% so this is indeed on the better end of the spectrum. These two teams were both actually incredibly good at handling the ball. The other Celtics-Lakers games I have from this year (not many to be honest) the rates are effectively the same. One Nationals-Hawks game had a much higher TOV rate, but another Celtics-Royals game is considerably good (~10%).

LikeLike