If there was ever an evolution of basketball that led to present day NBA, it would be the transformation of the misdirection offense starting in the early 2000’s under Spurs’ head coach Greg Popovich. Leading the charge in reducing the number of low percentage shots, spreading the court through a series of flare screens, drags, and horns action, the Spurs have built the gold standard for NBA offenses. One such play, which we will focus on today, is the Hammer Screen. This play, well known for the better part of the last five years as a San Antonio Spurs staple, is a microcosm of the layups and three’s philosophy that had taken the league by storm.

There’s a fantastic article from Doug Eberhardt at SBNation that details the Hammer Screen, leveraging a Fast Draw-type implementation sketched out by Zak Boisvert. Without going into the depth that has already been achieved by these writers, our focus will be on outlining the motion, identifying wrinkles that some teams put into the action, and then identify methods for analysis.

As there has been so much said about the Hammer for the Spurs, so much that SBNation has written two articles on the same subject (!!), I will make sure to not show a single Spurs action.

What Is Hammer?

The Hammer screen is a weak offensive maneuvering that frees a shooter while the defense’s focus is aimed to the strong side. The action is almost similar to a flare screen, where the player being screened pops out away from the key towards the three point line. However, the difference here is that the action is timed in coordination with distinct activity towards the basket on the strong side of the court. The goal? Pull the defense in to stop penetration from a guard, set the weak side screen on the shooter’s defender, and kick out across the court to the now-free shooter.

Los Angeles Clippers

Let’s take a look at an instance of the Los Angeles Clippers running the hammer. This is the famous 99-98 Clippers 27-point comeback win over the Memphis Grizzlies in Game 1 of the First Round of the 2012 NBA Playoffs. During this key run, the Clippers pulled out the Hammer:

In this play, the Clippers run a sideline screen action with Reggie Evans (#30 – LAC) setting the screen on Michael Conley Jr. (#11 – MEM) to free Chris Paul (#3 – LAC). If you recognize the start of this screen play, we covered this recently in covering the BLUE defensive scheme. In fact, we see the Grizzlies start out running BLUE! This forces Paul to go baseline, getting picked up by Marc Gasol (#33 – MEM).

As we see the BLUE defense, Gasol is beaten by Paul. Mareese Speights (#5 – MEM) is caught hedging at the Two-Nine, forcing him to make a decision: pick up Paul or cover Evans, who is running a Drag Screen down the lane. Turning his entire focus towards Paul, Blake Griffin (#32 – LAC) sets a high post weak-side (Hammer) screen on Rudy Gay (#22 – MEM) to free up Nick Young (#11 – LAC), who breaks for the corner.

In a play worked to perfection, Paul steps underneath the basket towards the sideline as Young slips into the corner. Paul hits Young with a quick pass as he exits out of bounds; leaving Young with 7 feet between himself and the closest defender. Young knocks down the three to cut the deficit to 9.

Indiana Pacers

The Indiana Pacers also run the Hammer screen but use different strong-side action to pull the defense in towards the paint. In this situation, the Pacers are down 94-103 to the Charlotte Hornets with 2:25 remaining in the game.

In this action, the Pacers post up with Paul George (#13 – IND) being guarded by Nicolas Batum (#5 – CHA). We see that Cody Zeller (#40 – CHA) hedges the Two-Nine; releasing off of Ian Mahinmi (#28 – IND) in case George spins towards the basket. By taking his focus off of Mahinmi, Mahinmi is now free to head hunt George Hill’s (#3 – IND) man, Kemba Walker (#15 – CHA). He does just that, freeing up Hill with a Hammer Screen as George spins towards the basket, drawing Zeller to the baseline for a double team. Throwing the ball across the court, Hille is open for a slightly contested three point attempt that cuts the lead to six with 2:14 remaining in the game.

The Pacers ultimately lost, 101-108.

Quantification: Three Basic Spatio-Temporal Analytics

Let’s take a look at how this play works. The action is almost always the same: A ball handler drives towards the basket, drawing a defense to collapse around the rim. A weak side defender is caught off guard by a screen, allowing a shooter to flare into the corner. The other two offensive players are wrinkles in this offensive scheme, free for a coach to design misdirection. Let’s map this action out.

Los Angeles Revisited

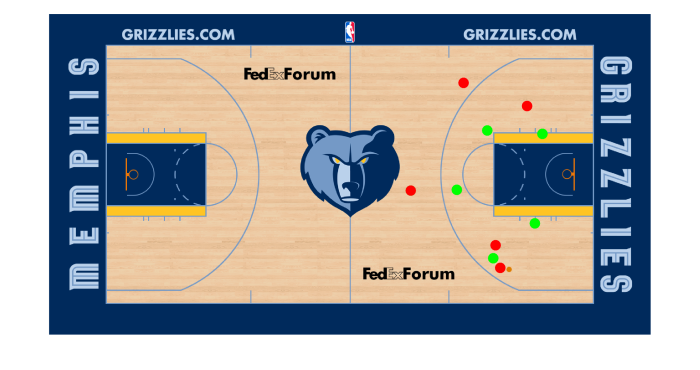

For the Clippers (Red) version of the play, a drag screen is executed in response to the BLUE defense ran by the Grizzlies (Green).

We see that the convex hull of the defense well covers the points of attack. The only question marks are the path towards the basket; where Marc Gasol is guarding the block after sagging on the screen… and the three point region where Nick Young is lingering on the weak side. Otherwise, this defense should lead to a low percentage field goal attempt.

For reference, Nick Young was a 36% three point shooter while Eric Bledsoe (#12 – LAC) was a 27% three point shooter (and rookie). This play breaks down because of two items: Gasol gets beat, forcing Speights to collapse.

Here, we see that the entire Grizzlies’ defense is covering the key and has large separation on two spots: Nick Young and Eric Bledsoe. Bledsoe, a low percentage shooter is lingering at 30 feet from the basket. Due to this, O.J. Mayo (#32 – MEM) opts to cover a low percentage shooter in an even lower percentage range; effectively covering no one on defense.

Instead by having Mayo opt to sag to the nail, this would have allowed Rudy Gay to sag on the passing lane. The analytic presence here is passing lane coverage.

Passing Lane Coverage

Passing Lane Coverage is a simple metric that identifies what percentage of time a player is in the passing lane regardless of location on the court. If we condition field goal attempts off of passes, this gives us insight as to how out-of-position a defensive player is from receiving a pass.

Let’s draw the passing line in both ends of the drive from Chris Paul.

In this case, Rudy Gay is within the passing lane. If Chris Paul were willing to make a pass of thirty feet, through three defenders, then Rudy Gay has this play well covered. Unfortunately, this is not the play. Therefore covering the passing lane is not the optimal play.

Here, we see that Gay is now far away from the passing lane. This is the initiation of Blake Griffin’s screening motion; hence the screen is not the root cause of this separation. The root cause here is O.J. Mayo not allowing Gay to sag along the passing lane. If Gay were to sag, Griffin’s screen would be on the low block; not the high post.

It should be noted that Mareese Speights is in the passing lane. But he really isn’t. This bit comes from scouting knowledge. A player that is in the passing lane must have the ability to have active hands in a passing lane. What this means is, if a defender closes out on a ball handler, they are no longer in an active passing lane, but rather a on-ball defense. This scouting knowledge typically translates into coaching speak as Man-You-Ball or Quarter/Third/Half-Way. In the case of Speights, he is too close to the ball handler to make a meaningful off-ball defense with respect to Nick Young.

Passing Lane Distance

A secondary analytic is the passing lane distance, or the number of feet for a defender to cover a passing lane between the ball handler and his respective man. This distance measures how far out of place a defender is from the play.

In this case, we find that Rudy Gay is just under six feet (5.74 feet) from covering position. We can measure this distance with a third analytic, which is called close out velocity.

Close Out Velocity: Pass

Close out velocity allows for an offense to know the recovery speed of a defender. The computation is relatively straightforward, however slightly more complicated that the previous two analytics. In this measurement, we take the time of flight of a pass and measure the distance traveled between the relative defender’s position at the start and finish of this time of flight. Taking the fraction of this quantity, we obtain feet-per-second recovery. For the roughly 20 games of SportVU data that we have for this, Tony Allen (New Orleans) and Avery Bradley (Detroit) are two of the fastest recovery men in the league.

Let’s be clear on this quantity. At the start of the pass from Chris Paul, Rudy Gay is located 12.974 feet from Nick Young. At the end of the pass, Rudy Gay is 9.379 feet when Nick Young receives the pass. While Rudy Gay has traveled a total of 8.474 feet; he has only closed out a relative 12.974 – 9.379 = 3.595 feet over 0.66 seconds for a rate of 5.44 feet per second. Compare this to a Tony Allen, who habitually is over 7 feet per second.

This means that on this play, Gay has a close-out rate of 5.44 feet per second. This means, as a coach on offense, you identify sets that spreads fast defenders out such that passing lanes open up; or lighten up on slower defenders to ensure a better opportunity to rebound. In this case, Gay closed out on the play better than an average player and still was unable to harass Young into a miss.

I encourage you to try this for the Pacers example above!

Hammer Wrinkle: Timberwolves Get Crafty

Let’s take a look at a player who actually covers the Hammer so well, that he leaves his team out to dry. In a game between the Minnesota Timberwolves and the Los Angeles Lakers on February 2nd, 2016. Down 5 with 13 seconds to play, the Timberwolves go straight into the Hammer with Ricky Rubio (#9 – MIN) speeding towards the baseline.

Once again with the sideline screen action, the Lakers are not quite in BLUE position and find themselves in a double team. The screener, Karl-Anthony Towns (#32 – MIN) stays high and out of the play. Despite being a rookie big-man, Towns is still a 34% three point shooter and is a pop-threat in a close contest.

Brandon Bass (#2 – LAL) and Lou Williams (#23 – LAL) are the trap men. Williams getting screened and Bass leaning too far, allows for Rubio to speed to the rim. This forced Julius Randle (#30 – LAL) to cover the Two-Nine, abandoning Gorgui Dieng (#5 – MIN) to set the hammer screen at the high post on Jordan Clarkson (#6 – LAL), freeing Zach LaVine (#8 – MIN) to sprint to the corner.

However, instead of fighting through the screen, clarkson darts for the passing lane, as a tipped pass out of bounds stops the play and forces the Timberwolves to restart the offensive position with less than 10 seconds left in the game. Dieng and Rubio, seeing this, get a brilliant dump pass for an easy lay-up.

The question is then, who blew the coverage?

The Answer Is Not So Simple.

To be clear, Jordan Clarkson busted the hammer screen; saving the Lakers for a potential three point field goal from a 39% shooter. Best on the court for the Timberwolves.

Brandon Bass, found himself in terrible recovery; unable to slow Rubio down. After allowing Rubio to pass and forcing Randle to effectively cover Rubio, Bass stayed outside of the lane to guard Towns; who would have required a miracle pass from Rubio (oppositie direction). Kobe Bryant (#24 – LAL) strayed at the top of the key to guard an unknown player. Who was that player (who was so far out of frame, that we never see him)? Andrew Wiggins (#22 – MIN), the one who struggled to shoot 30% from the arc.

Taking a look at the coverage, an argument can be made that Bryant could have covered Dieng. Moreso, stepped in front of him, a difference of four feet separating them. Had the pass gone to Wiggins, the pass would have needed to clear Bryant, who would have been in the passing lane, to a low percentage shooter who was ten feet beyond the arc.

However, we won’t call out Bryant as he’s won more than enough games in his lifetime; including this game as the Laker prevailed 115-111.

However, we can apply these analytics (passing lane coverage, passing lane distance) to show how coverage performs well (Clarkson) to take away the three point attempt; as well as other analytics (convex hull coverage) to show how break downs occur. In this case, Dieng punctures the convex hull at a high probability shot region; allowing for the Hammer wrinkle to breathe life in a Timberwolves come-back with 9 seconds remaining.

Thoughts?

So now that we see how we can measure defenses in the Hammer, how would you draw up a defense to stop it? How would you build personnel to slow the offense down and anticipate the plays?

These are simple measures; we can even take a step further to build predictive analytics. But we can save that for a later date.

Pingback: Hammer Offense: Mechanics and Quantification by Justin Jacobs of Squared2020 | Advance Pro Basketball

Pingback: Building a Simple Spatial Analytic: Passing Lane Coverage | Squared Statistics: Understanding Basketball Analytics

Pingback: Measuring Attack Vectors of Ball-Handlers | Squared Statistics: Understanding Basketball Analytics